Eugene Joe: Synonymous With Navajo Sand Art Painting

Eugene Joe: Synonymous With Navajo Sand Art Painting

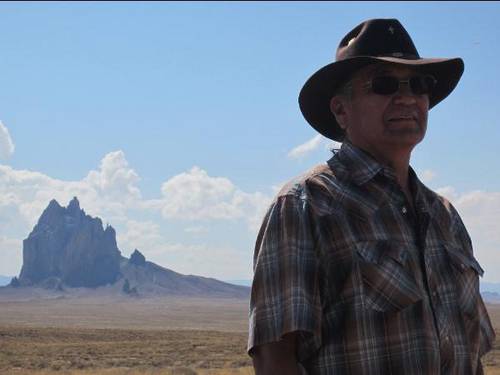

A stiff wind lifts Eugene Baatsoslaani Joe’s heavy ponytail as he gazes across the vista that first inspired him more than half a century ago.

It’s not hard to find a quiet place to ponder among the sandy hills in the northwest corner of New Mexico, but this mesa is his: a place Joe staked out for himself as a child and a location he visits often as an adult.

The view near Shiprock, New Mexico, has changed over the years: power lines chase the horizons, dirt roads cut across the landscape and a water tank sits atop the mesa where Joe discovered his destiny.

“I sat here until I knew what I was supposed to do with my life,” he said. “I sat here until the insects were crawling over me and I was one with the earth.”

Joe, whose name is synonymous with contemporary Navajo sand painting, decided when he was very young that he would use art to capture that harmony with the earth and with his Native traditions. He has spent nearly 50 years making a name for himself as an American Indian fine artist.

At 63, Joe still returns to this mesa for inspiration and meditation.

“This is where philosophers, thinkers, men who want to be men, this is where they are born,” he said. “I sit here on top of the mesa, not thinking, not meditating, not wanting, but just seeking to blend in.”

Joe started his artistic journey as an apprentice to his father, James C. Joe, who was a pioneer in Navajo sand art.

Traditionally part of sacred healing ceremonies inside Hogans, sand paintings are performed by medicine men and are not intended to last more than a couple of hours. Sand paintings are called “ikaah” in the Navajo language, or “a summoning of the gods.”

Medicine men use sand on the floor of the Hogan to create designs and figures in the five sacred colors: white, blue, yellow, black and red. A patient sits on a completed painting and the medicine man touches the sand figures and the patient to transfer the medicine.

The sickness then falls away and conditions of harmony are restored. The sand painting is erased before sunset, and as the sand is disposed of, the last of the sickness is carried away from the patient.

James Joe was among the first Navajo artists to transform sand painting into a contemporary medium by using glue to fix the sand to boards. A medicine man, or hatathli, James Joe also helped set the parameters for what was acceptable when it came to turning a sacred healing art into a fine art.

James Joe faced resistance from tribal elders, said Ed Foutz, former owner of Shiprock Trading Company. Foutz jumped at the opportunity to market fixed sand paintings and was the first to buy and sell them.

“There was some feeling that it shouldn’t be done,” Foutz said of the early paintings, which some elders viewed as disrespectful. “When (the artists) came in, they brought them in covered, or quietly. They were bought in a separate room – a safe – where other people didn’t see them. There was feeling that things like that shouldn’t be put on boards.”

After trading with James Joe for several years, Foutz bought a painting from Eugene Joe in 1967, when the artist was still a teenager. Although Foutz doesn’t remember the specifics of that first painting, he does remember the artist.

“Eugene was fairly shy as a teenager,” Foutz said. “I remember him coming in with his dad and he didn’t say much.”

In 1972, Joe enrolled in classes with a professional artist named Don Esley, of Maine, who encouraged Joe to develop his own style. Training as a fine artist helped Joe carve a niche that has sustained him through years of economic instability and in the face of dozens of imitators.

Sand painting grew in popularity in the 1970s, Foutz said. While Joe was cultivating his talent and planning for a future as a serious artist, hundreds of other sand painters flooded the market.

“Back then, you bought sand paintings from one or two people, then all of a sudden there were thousands of them,” Foutz said. “There were so many I used to joke that they would use up all the sand and the community would cave in.”

Joe worked steadily to perfect his techniques, ignoring the artists who mass-produced paintings and sold them to tourists.

“So many of the sand painters got a particular pattern or did different figures and just reproduced them in different sizes,” Foutz said. “Eugene started down his own road. Instead of being just another sand painter, he had some talent and went on to perfect it. It got extremely – beautifully – artistic.”

Another thing that sets Joe apart from other artists is his knowledge and reverence for Navajo traditions in his paintings, said Mark Bahti, of Tucson, Arizona. Bahti has spent his career showing and selling Indian art, and he co-authored with Joe several books about Navajo sand painting.

Because his father was both an artist and a hatalthli, Joe learned the sacred nature of sand painting and how to represent Navajo tradition in contemporary art.

“Eugene was the one breaking the new ground when it came to sand painting,” Bahti said. “Most craftspeople don’t understand what they are representing. They use designs they see in books instead of relying on the traditional background. Sand painting has become the fast food of Indian art. It is appeal without description.”

Joe avoided that by recognizing that contemporary sand art should not include exact reproductions of the sacred healing ceremony, but that it can still honor the traditions and the elders, Bahti said.

“He is not reproducing ceremonial sand art on a canvas,” Bahti said. “He leaves out key elements or sequences so it’s not an exact reproduction.”

An exact reproduction of the ceremonial painting would summon the gods, who are required to answer prayers if they are offered correctly, down to the smallest detail. A fixed sand painting risks offending or mocking the gods, which can lead to harm.

Sand painting as a fine art requires small alterations, Bahti said. Examples of this include substituting a prescribed color with another one, leaving out one of the four sacred plants or changing the number of feathers on the heads of the Holy People.

“Sand painting is generally regarded as risky,” Bahti said. “Eugene pushes the limits. He took his training as a fine artist and moved it forward as a technique instead of a craft.”

From an early age, Joe decided to make religious paintings, but he also wanted to expand his portfolio by capturing portraits, landscapes, nature and traditional lifestyles. He also does profiles of warriors, collages and glues smaller sand paintings on top of larger ones for a three-dimensional effect.

Joe learned from his father the painstaking techniques – an education that lasted six years before Joe started making his own paintings. That included learning the process for grinding stones into sand and sifting the sand between his fingers.

“The art form changes from artist to artist, but the traditional form is passed down from master to apprentice,” Joe said. “That’s why my father was so important to me.”

Joe treated his chosen medium the way any artist would, he said. His first pieces were simple, but as the years went on, they became more complex and incorporated more artistic elements.

“I’m always pushing the boundaries, trying to figure out what else I can put on canvas,” Joe said. “Over the years I have added more details, more textures, more colors than ever before. Now I am looking for techniques that other painters can learn and use. The old masters used oil, pastels, sculpting, weaving and pottery. Now sand painting is emerging as its own medium, so that means I have to push it and see where I can make it go.”

That drive is something traders and collectors recognize in the paintings, Foutz said.

“Eugene has a wonderful artistic ability and is always trying to become better,” Foutz said. “He is always looking for different colors of rocks that he can grind down, looking for techniques to add to what he is doing. He is never satisfied.”

Nearly 50 years after he sold his first painting, Joe’s career shows no signs of slowing down.

Interest in sand painting has dipped along with the economy, Foutz said, but Joe continues to sell.

“From a standpoint of marketability, Eugene is right at the top,” Foutz said. “Eugene today is one who can sell. He can take his work out and return empty-handed. Sand painting may not ever reach the same level or be as accepted as oil paintings or sculptures, but Eugene is one who can sell.”

Steve Mattoon, manager of Garland’s Navajo Rugs in Sedona, Arizona, is one of Joe’s biggest buyers. Mattoon has bought and sold Joe’s work for the last 32 years and usually has about half a dozen in stock.

Mattoon sells to novice art buyers and to collectors alike.

“People respond to his imagery and his color and the quality of his work,” Mattoon said.

“Eugene’s unique style and the amazing quality of his work has been time-tested for 32 years.”

A découvrir aussi

- LEELA -Let's Spirit Dance - together

- Weekly news and views from around the world and beyond.

- Nous avons testé « Graph Search », le nouveau moteur de recherche sur Facebook